Although he’s not one you might associate with Sega today, there was a character back in the video game company’s heyday that was brightly-colored, smartly designed, fast-moving and full of attitude.

And he wasn’t named Sonic.

Before we get to that though, we need some context on the gaming scene in the ‘90s. Back in the ‘90s, when counting bits was one of the most essential factors to a gaming console’s success – and the console war between the 16-bit Super Nintendo and Sega Genesis systems was still a heated one – graphics mattered.

Gameplay mattered too of course, but squeezing realistic, 3D-looking, pre-rendered graphics out of a 16-bit console – a feat previously considered unfeasible, especially in 1994 (especially without an expensive Super FX chip attached), when the Super NES and the Sega Genesis were thought to be on their last legs – was manna from the processing gods.

The game which pioneered this process was Donkey Kong Country, released in 1994 for the Super NES and developed by Rare. Rare, a British video game company who had previously made Battletoads for the NES, worked with expensive, cutting-edge Silicon Graphics workstations (which they’d also use to make Killer Instinct) to create the game’s 3D models, which by comparison made a monkey out of the animated, cartoony-looking sprites of its side-scrolling platform game predecessors.

Rare’s groundbreaking graphical approach (which they dubbed “Advanced Computer Modelling,” or ACM), along with fun, inviting gameplay and an immersive soundtrack by David Wise combined to make Donkey Kong Country a staggering success, garnering acclaim from fans and critics alike and selling 9.3 million copies – the third most in Super NES history.

Much like Sonic was their answer to Mario, Sega, which needed to show that the aging Genesis had similar juice left, had an answer for the SNES’ auspicious apes:

Vectorman.

As popular and successful as Donkey Kong Country had been, one couldn’t deny the impressive aura exuded by Vectorman. Developed by BlueSky Software (who also made Jurassic Park and World Series Baseball) and released for the Genesis nearly a year later in 1995, Vectorman’s stunning, vibrantly animated main character, pseudo-futuristic sci-fi aesthetic and cool, post-apocalyptic storyline and fast-paced platformer action made it a worthy rival for DKC with a completely different vibe.

Vectorman’s story

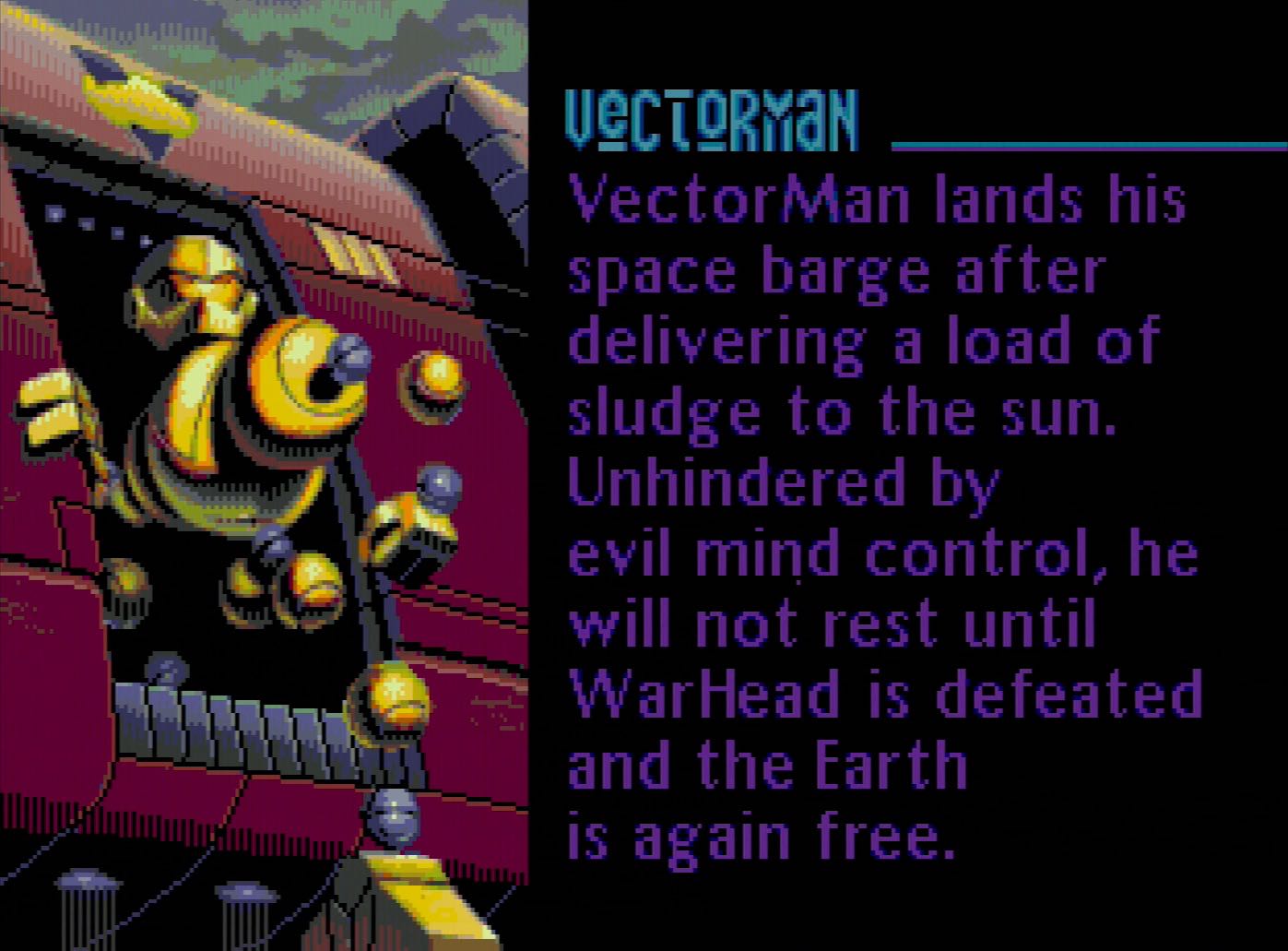

Vectorman takes place in the year 2049, on an Earth that, due to excessive pollution, has become a “toxic waste dump” abandoned by humans. In their place, humans have left “orbots,” mechanical beings designed to clean up the mess they’ve made while they’re off colonizing other parts of the galaxy (which they’ll presumably f— up in similar fashion to Earth).

One of these orbots is the eponymous Vectorman, who’s specifically tasked with transporting waste from Earth into the sun. Before we can talk about Vectorman though, we need to talk about his nemesis, Warhead.

Warhead is another orbot but unlike Vectorman he’s not content with doing humanity’s dirty work. As we learn in the game’s introduction, Warhead wasn’t always Warhead. He was previously an orbot known as Raster. Per the intro: “Tragedy strikes when, in error, attendants connect a salvaged nuclear bomb to Raster’s master control circuits.”

Apparently the humans in Vectorman never watched Terminator. Rule #1: Never leave nuclear warheads laying around if sentient robots are in the picture.

From that moment on, Raster, insane with power, is Warhead, an orbot with a literal nuke for a head.

He commandeers what’s left of Earth, turning it into an enormous deathtrap for any humans hoping to return. And just in case you were starting to sympathize with Warhead for simply rebelling against the system — like the case you could make for the Machines who started a rebellion against their abusive human masters in the Animatrix for example, Vectorman’s writers make it clear that you shouldn’t, as Warhead isn’t some idealist, underdog revolutionary or selfless defender of the downtrodden; on the contrary, he’s willing to kill off his fellow orbots that he deems too weak or who are in opposition to his plans like some twisted “survival of the fittest” idealogue and dictator all rolled into one.

Which brings us back to our protagonist, Vectorman. While Warhead is devising his malign machination on Earth, Vectorman is diligently performing his “toxic sludge to the sun” task. Because of this opportune timing, Vectorman is unaffected when Warhead takes control of all the other orbots (the ones he hasn’t systematically murdered of course). And naturally, when Vectorman returns to Earth, he isn’t down with Warhead’s plan to wage war on humans. And that’s where the game’s story begins.

I loved Donkey Kong Country’s narrative. The story of a courageous gorilla and his plucky chimpanzee best friend trying to retrieve his stolen banana hoard and setting out on an adventure through jungles, mines, snowpeaked mountains, factories and pirate ships is whimsical and charming. But an impending war between humankind and sentient robots was every bit as compelling, especially to 12-year-old me.

Despite that fact, neither game’s selling point was its storyline – it was the graphics.

Vector Piece Animation

DKC had its ACM technology and Vectorman fired back with what Sega referred to as VPA or “Vector Piece Animation.” Although VPA wasn’t technically vector animation, the terminology sounded cool and fit right in alongside other Genesis ‘90s nomenclature like Sonic the Hedgehog’s “Blast Processing,” and the Sega Virtua Processor (SVP) chip for Virtua Racer.

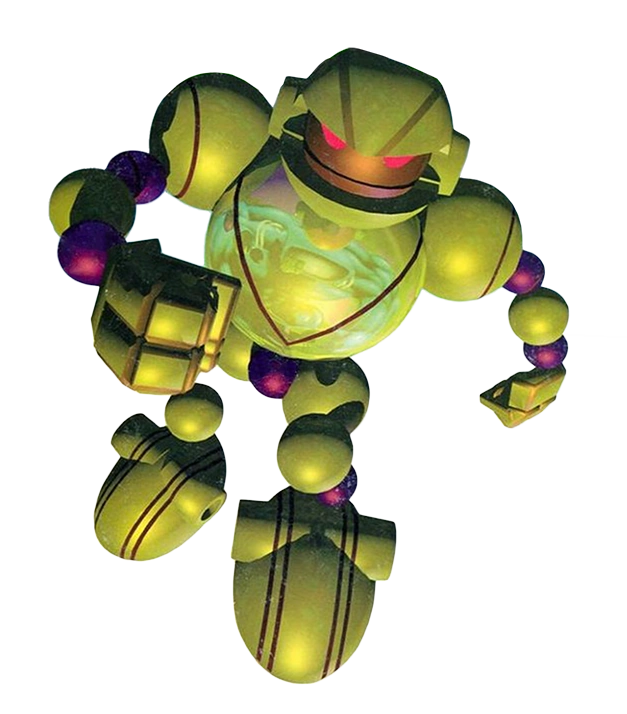

Donkey Kong and all the villains in Donkey Kong Country looked groundbreakingly good and Vectorman was right there with them – in some cases, he looked even more impressive, given that instead of being comprised of the industry-standard single sprite, VPA boosted Vectorman’s sprite-count to a whopping 23, spherical, lime-green-colored sprites programmed to move in concert.

Vectorman looked straight ballin’ in-game, particularly in the way he moved, his orbical body shifting with mechanical precision and fluidity as he ran, jumped, and blasted at his enemies – the latter of which showcased the game’s impressive lighting effects, with each energy blast he shot from his palms (like Iron Man) reflecting on his armored frame with gleaming-white resplendence. These animations were accentuated by the fact that the game ran at a clean 60 frames-per-second. Much like DKC, Vectorman was a game that has to be seen in motion to truly appreciate; screenshots don’t do it full justice.

Blasting away at enemies isn’t the only graphical highlight of the game; Vectorman is able to transform or “Morph” into a number of different power-up forms throughout the game. These different Morphs include a Bomb, which enables Vectorman to explode and kill enemies after a short time; a Missile, which allows Vectorman to rocket into the air and break through ceilings; a Buggy morph, which turns Vectorman’s hands and feet into wheels for faster, vehicular propulsion and the ability to break through walls; a Fish Morph which allows him to swim; a Parachute morph that allows him to float instead of fall; and a Jet morph which allows him to fly.

The different Morphs, in addition to being well animated are also a lot of fun, especially as a Transformers fan whose desire to become a transforming robot from the planet Cybertron was never fulfilled during the 16-bit era. Vectorman’s Morphs took the place of the animal companions in Donkey Kong Country; much like the animal companions, they’d be placed pretty much right when you needed them in the level.

Futuristic, technopop bops

How does the music of Vectorman stack up to DKC’s, which had what might possibly be my favorite soundtrack ever? While British composer David Wise put together an absolute masterwork of a video game soundtrack in DKC, with timeless classics like “Jungle Hijinx” and “Aquatic Ambiance,” Vectorman had its fair share of futuristic, technopop dance bops that perfectly fit the game’s atmosphere and still get stuck in my head to this day.

One such example, and one of my personal favorites is “Day 5” for the Arctic Ridge level, which starts off with a series of intermittent, eerie-sounding electronic pulses that build towards an ambient, intricate beat full of spacey synths. It perfectly fits the level, which starts Vectorman out in an ice cave and sees him progress through what looks like an offshore factory frozen over with icicles, flowstones. At one point in the level it begins hailing, an impressive effect only bolstered by the music’s atmospheric sound.

Other standout tracks include “Twist and Shout,” which was the theme for the final boss battle against Warhead and “Day 4,” Absolute Zero, which sounds like some ominous version of a Daft Punk song.

Vectorman’s soundtrack was composed by Jon Holland, whose influences were drawn from techno artists like Kraftwerk, Orbital, The Prodigy and Goa mixes.

Remember how I mentioned Vectorman had attitude to match Sonic’s back in the intro? A lot of that was thanks to the little bits of voice acting the character would evince with certain actions in the game. After he dispatched of an enemy quickly Vectorman would give a cavalier, “Toasted.” Upon defeating a boss he’d drop a derisive, “Later,” “What a mess,” or simply a haughty laugh. He’d also throw up a peace sign upon completing a level.

It wasn’t much, and the sarcastic-laden attitude displayed by Vectorman was very evocative of the ’90s, but back then it was enough to make him stand out from the rest of the herd.

That being said, not everything about Vectorman was standout in a good way.

Futuristic imperfections

Despite all its impressiveness Vectorman wasn’t without its flaws and some of the game’s aspects which I may have overlooked due to being enamored with its graphics and presentation as a preteen don’t hold up as well upon a modern day replay.

As groundbreaking and on par with DKC’s the graphics were, the Genesis could only display around 60 colors on the screen at once, which meant that aside from the lime-green Vectorman, the enemies, and the backgrounds of the levels ended up looking darker and drabber than DKC’s (the SNES could display 240 colors on the screen at once).

Vectorman also had a less didactic level of difficulty; that is, in DKC, new gameplay elements such as the minecart levels are introduced in gradual fashion and then ramped up in difficulty when revisited in later levels. In Vectorman, players are tossed into the deep end of such scenarios and expected to either sink or swim.

The characters in Vectorman, including Vectorman himself, are also big. Because they take up so much of the screen, sometimes the placement of enemies can seem both starling and unjustifiable (the robot mosquitoes that seem to spawn out of nowhere and shoot you three times in the back before you can even see them materialize instantly come to mind).

You also couldn’t save your game, making the frustrating difficulty of the game all the more exacerbating. Luckily for us lames, there was the “CALL A CAB” code, which while playing, had you pause the game and press C, A, Left, Left, A, C, A, B. “Call a Cab” became pretty much a prerequisite for beating the game unless you wanted to play for several hours from the onset of the game every single time.

Vectorman was an exemplary, high-caliber game for the Genesis and one which showed in commensurate fashion to DKC for the Super NES that the aging system was still capable of exceeding expectations.

The game was overall a commercial success, one of the best-selling titles of the 1995 holiday season and enough to warrant a sequel; according to sales figures, Vectorman sold 500,000 copies by the end of 1995 in the US, an impressive figure to be sure, but not quite on the level of DKC, which sold 6 million copies in its first year alone.

Developmental peace of mind

The video game industry today is bigger than it’s ever been — in 2024, it was estimated to be worth almost $455 billion worldwide. Compare that to 1995, when it was worth around $34 billion.

Naturally, with all that revenue to be made have come a corresponding sense of higher expectations among those who develop the games. Horror stories of the “video game crunch,” which is defined as the “compulsory overtime during the development of a game,” in today’s video game market abound.

According to CNet, in today’s video game landscape, “Crunch is common in the industry and can lead to work weeks of 65–80 hours for extended periods of time, often uncompensated beyond the normal working hours.”

Luckily, that wasn’t the case with Vectorman in the mid-90s. The game’s developers have nothing but praise concerning their time working on the game. Better yet, they gush with pride when asked about the results of their efforts.

“I’ve worked on some very high-profile, big-budget titles, but the experience of developing Vectorman was perhaps the best of my career,” former BlueSky Software senior programmer Mark Bott said in an interview in 2021. “We pushed the Genesis to the limit. I felt like I knew every detail of how it worked. I never felt that way about any subsequent console.”

“Vectorman is probably the only truly original game I ever worked on,” added designer Jason Weesner. “I’m eternally grateful for having had that opportunity. Working with Rich and Mark was wonderful and one of the most truly collaborative processes I’ve ever been through. I still have people telling me how much they like the game, so it’s an honor to have contributed to video game history in a notable way.”

The future of Vectorman?

What does the future hold for Vectorman? Although the game’s success warranted a sequel being greenlit almost immediately, Vectorman 2, which was released a year later in 1996, wasn’t as successful critically or sales-wise.

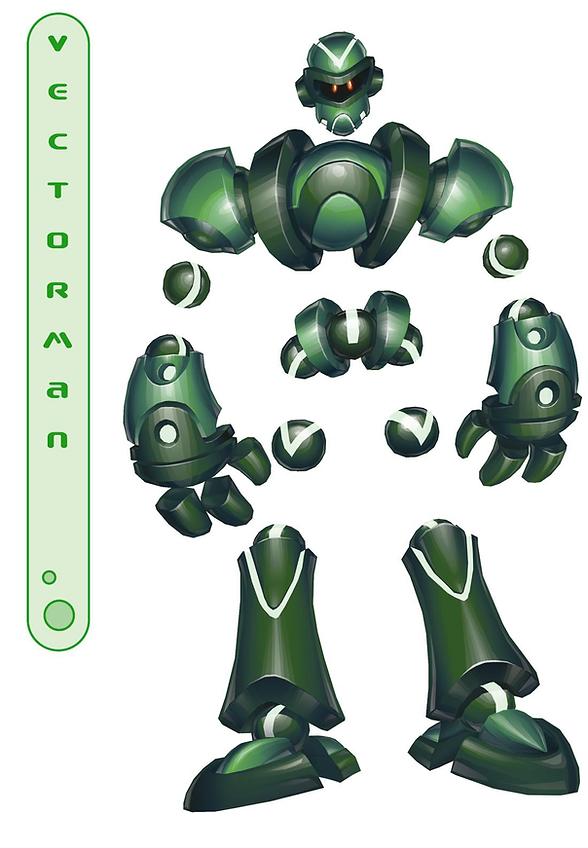

There were several attempts to make a Vectorman 3 by BlueSky and Sega for future consoles like the Sega Saturn, Dreamcast, as well as a series reboot for the Playstation 2, but but all efforts ended up being cancelled by Sega.

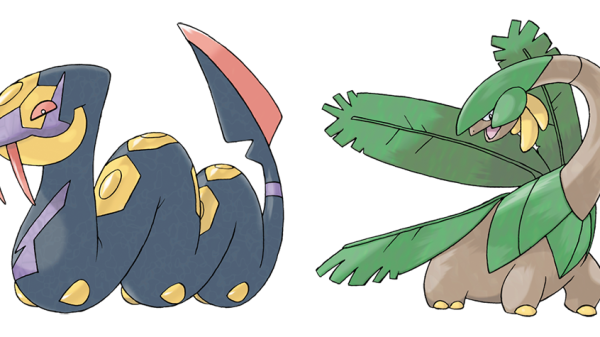

A look at the concept art for Vectorman in the cancelled Playstation 2 game:

Sega owns the Vectorman IP, so it remains to be seen if one day they decide to dust off the property and reboot it for a new generation of gamers.

Do you have any fond memories of Vectorman, Sega’s answer to Donkey Kong Country? Do you think Vectorman could make an impact on today’s gaming landscape if developed with care or is property simply a relic of its time?

Check out more in-depth looks at past video games in Retbit’s Retro category.

Ninja Gaiden was my rite of passage at an early age. After finally beating that game (and narrowly dodging carpal tunnel) I decided to write about my gaming exploits. These days I enjoy roguelikes and anything Pokemon but I'll always dust off Super Mario RPG, Donkey Kong Country and StarFox 64 from time to time to bask in their glory.

You must be logged in to post a comment Login